Understanding the 'Why' Behind Big Emotions: Trauma-Responsive Parenting in Adoption

Children with trauma histories often present behaviors that defy logic—meltdowns, shutdowns, and aggressive outbursts that can catch even experienced caregivers off guard. The key to understanding these behaviors lies not in controlling them, but in decoding the stress, fear, and past trauma that fuel them. This article offers a trauma-informed roadmap to support healing and resilience for children in adoptive and foster care.

What Is Trauma?

Defining Trauma

Trauma, especially in the context of childhood and adoption, is not just about what happened—it’s about how the child experienced what happened. Trauma is any event—or series of events—that overwhelms a child’s ability to feel safe, understood, or in control. It shatters their sense of security and stability.

While it’s common to associate trauma with severe abuse or catastrophic events, trauma also includes what’s often overlooked:

Chronic neglect that leaves a child emotionally starved

Separation from primary caregivers, even at birth

Frequent transitions—moving from home to home, school to school

Medical procedures or hospitalizations that happen without emotional support

Witnessing violence or addiction, even if not directly harmed

For adopted children, trauma can begin before birth—with prenatal stress, substance exposure, or maternal distress. It can continue through foster placements, court proceedings, or simply the grief of losing a birth family. Trauma is both the event and the lasting echo it leaves in a child’s body, mind, and spirit.

The Neurobiological Impact

Trauma changes the brain. It’s not a metaphor—it’s neuroscience.

When a child is consistently exposed to stress or fear, their brain develops a heightened sensitivity to perceived danger. The amygdala—the brain’s alarm system—becomes overactive. It’s like a smoke detector that goes off not just for fires, but for burnt toast, loud voices, or someone standing too close.

Meanwhile, the prefrontal cortex, the brain’s center for reasoning, planning, and impulse control, is underdeveloped. This means children impacted by trauma may:

React explosively to small frustrations

Struggle to understand consequences

Have difficulty transitioning from one activity to another

Appear “manipulative” or “oppositional” when in fact they’re overwhelmed

Their nervous system is doing what it was designed to do: protect them from harm. But in safe environments, that survival mode becomes a barrier to connection, learning, and emotional regulation.

Understanding these neurological realities helps shift the caregiver’s perspective from “what’s wrong with this child?” to “what happened to this child—and how can I help them feel safe?”

Behavior as Communication

Children rarely say, “I’m scared.” Instead, they throw chairs, slam doors, or go silent. That’s not disrespect—it’s distress.

Trauma compromises a child’s ability to use words, especially in moments of emotional overwhelm. Instead, the body speaks. The nervous system speaks. And behavior becomes the message.

Behaviors we label as “bad” are often attempts to express:

Fear of abandonment

Unmet sensory needs

Confusion or shame

Hunger, exhaustion, or overstimulation

Triggers from past trauma that they can’t name or understand

When adults interpret behavior as willful defiance, they’re more likely to react with punishment. But if we decode behavior as communication, we respond with empathy and curiosity: What is this child trying to tell me?

This perspective doesn't excuse harmful actions—but it reframes them. It moves us from control to compassion, from correction to connection. Behavior is a flashlight—it shows us where healing is needed.

The Window of Tolerance

The “window of tolerance” is the emotional zone in which a person can manage stress effectively. Inside the window, a child can think, learn, engage socially, and use words to express needs. Outside of it, those capacities shut down.

Trauma narrows this window. A child who seems “fine” one moment may explode the next—not because they’re unpredictable, but because their nervous system shifts into hyperarousal (fight/flight) or hypoarousal (freeze/collapse) with very little provocation.

Signs a child is outside their window:

Hyperarousal: yelling, running, hitting, intense defiance

Hypoarousal: zoning out, going silent, withdrawing, appearing “checked out”

Traditional approaches often miss the signs and interpret dysregulation as misbehavior. But trauma-informed care focuses on expanding that window over time—through safety, co-regulation, and repeated relational repair.

As caregivers, our job is to become a child’s emotional thermostat. When we stay grounded, we help widen their window. When we attune to their needs and rhythms, we teach their nervous system it doesn’t have to be on guard all the time.

Learning to spot when a child is nearing the edge of their window—before they cross it—is a powerful tool. It allows us to intervene with calm, prevent escalation, and build trust moment by moment.

Trauma-Responsive Parenting

When parenting a child with a trauma history, traditional parenting strategies often fall short. Trauma-responsive parenting recognizes that regulation, connection, and safety are the foundation—not control or consequence. Healing takes root not through punishment, but through relationship.

Safety and Predictability

For children impacted by trauma, unpredictability is terrifying. Even minor changes in routine can be perceived as threats. That’s why consistency is therapeutic:

Predictable routines create a sense of control. Use visual schedules or gentle reminders to prepare for transitions.

Clear expectations give the child a framework to navigate their world. Keep language simple and directives gentle.

Calm responses de-escalate conflict. Instead of matching their energy, ground yourself—your emotional tone sets the atmosphere.

Emotional safety means a child can express big feelings without fear of judgment or rejection. It means knowing that even when they lose control, you won’t.

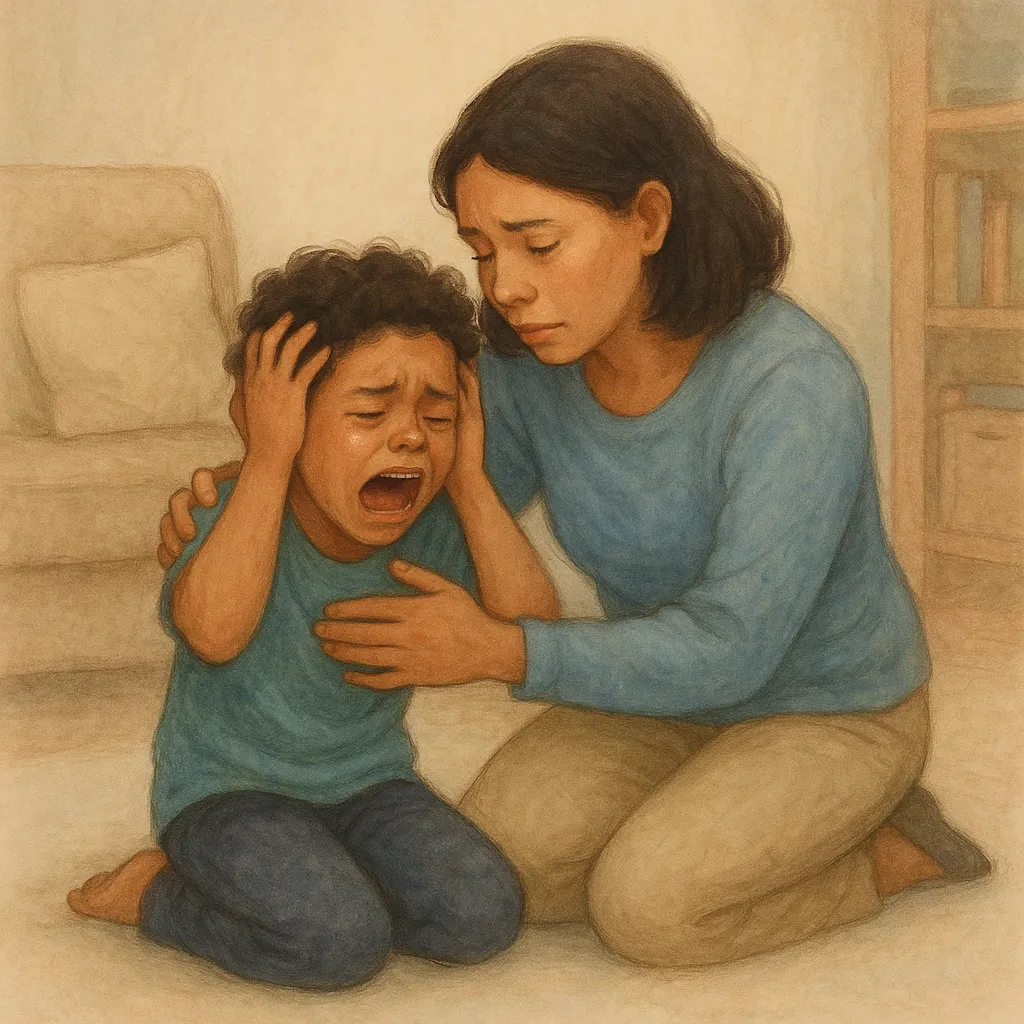

Connection Before Correction

Correcting behavior without connection increases shame. Connection isn't about ignoring behavior; it’s about seeing the child before addressing the behavior.

Attune first: Notice facial expressions, body posture, tone of voice. Is the child angry—or scared?

Use a calm tone and soft body language to signal safety. Avoid standing over them or using loud commands.

Validate feelings before offering redirection. “You seem really frustrated right now. I’m here to help.”

This approach doesn’t make children less accountable—it makes them more able to hear and receive guidance, because they feel emotionally safe enough to do so.

Co-Regulation Strategies

Children don't learn regulation through lectures—they learn by experiencing your calm in the midst of their chaos.

Breathing tools: Model slow breathing. Use props like pinwheels or feathers to make it engaging.

Sensory supports: Weighted blankets, fidget tools, or soothing textures help ground the body.

Calm-down spaces: A designated area with comforting items can offer a safe haven when emotions run high.

Importantly, co-regulation requires that the adult stays regulated. If your stress levels spike, the child’s nervous system will sense it. Taking care of your own emotional health is not optional—it’s essential to the healing process.

Building Attachment and Trust

Children from trauma backgrounds often enter adoptive or foster homes with disrupted attachment histories. They’ve learned that adults are unreliable, inconsistent, or even dangerous. For these children, trust is not assumed—it’s earned.

Consistency Builds Security

Trust grows in the soil of predictability:

Show up at the same times. Be the one who picks them up. Keep your word, even in small things.

Don’t withdraw your love when they misbehave. They need to see that your presence is not conditional.

Every time you do what you said you would, you tell the child, “You can count on me.”

Respect Their Autonomy

Attachment doesn’t mean smothering. Some children may be physically affectionate, others may recoil from touch. Honor their cues:

Let them choose how to receive affection—fist bumps, notes, shared activities.

Don’t force eye contact, hugs, or emotional expression. Let them lead at their own pace.

This tells the child, “You are in control of your body and your boundaries. I will respect you.”

Repair Ruptures Quickly

Attachment is not about never making mistakes. It’s about how we respond after the mistake:

If you lose your temper, apologize sincerely. Let them see that adults make repairs.

If you misunderstand them, reflect and reconnect. “I thought you were being defiant, but maybe you were just scared. I’m sorry.”

These moments teach that relationships are safe—even when things go wrong.

Create Opportunities for Shared Joy

Attachment grows not just through managing crisis—but through shared, positive experiences:

Play together, laugh together, explore nature or cook a meal.

Let the child lead in play—follow their imagination, not your agenda.

Shared joy builds a relational bank account. When conflict arises, you’ll have trust to draw on.

Be Patient with the Process

Trauma slows the development of attachment. Don’t rush it:

Some children may take months—or years—to trust.

Celebrate small signs of connection: making eye contact, asking for help, showing affection.

Your job is not to force attachment, but to show up daily as someone trustworthy, even when the child pushes you away.

Building Resilience

Resilience isn’t about never falling apart—it’s about learning how to recover, adapt, and grow stronger over time. For children who have experienced trauma, resilience is built not in isolation but in the presence of safe, loving, and emotionally available adults. It’s cultivated one moment, one interaction, one success at a time.

Support Self-Regulation Through Co-Regulation

A child cannot regulate emotions they don’t yet understand or haven’t seen modeled. That’s where co-regulation comes in:

When your child is dysregulated, focus on staying grounded yourself. Your calm presence is their emotional anchor.

Offer physical and emotional cues: slow breathing, gentle voice, relaxed posture.

Use moments of dysregulation as opportunities to teach regulation, not punish emotional overwhelm.

Resilience starts when a child realizes, “Even when I feel out of control, someone I trust can help me come back.”

Encourage Emotional Expression Without Shame

Many trauma-impacted children have been punished or ignored when expressing big feelings. To build resilience, we must welcome emotions, not silence them:

Create safe spaces for emotional release—through play, art, storytelling, or quiet presence.

Acknowledge emotions without minimizing them: “That sounds really hard,” instead of “You’re overreacting.”

Normalize all emotions—anger, sadness, fear—as part of being human.

This tells the child, “Your feelings are safe with me. You don’t have to hide to be loved.”

Promote Autonomy Through Shared Decision-Making

Trauma often robs children of choice and control. Rebuilding their sense of agency fosters strength:

Let children make age-appropriate decisions: what to wear, what to eat, how to decorate their space.

Ask for their input on family routines or problem-solving: “What do you think we should do about that?”

Avoid rescuing or over-controlling—guide them to solutions, rather than solving everything for them.

Each decision builds the belief: “I have a voice. I matter.”

Model Healthy Coping and Self-Care

Children learn more from what we do than what we say:

Practice your own emotional regulation—take deep breaths, set boundaries, apologize when needed.

Talk about your coping strategies: “I’m feeling frustrated, so I’m going to step outside and take some breaths.”

Let your child see that self-care is not selfish—it’s necessary. This gives them permission to do the same.

A resilient family is built on the well-being of everyone in the home—not just the child.

Celebrate Effort and Growth, Not Just Outcomes

Children impacted by trauma often struggle with perfectionism or internalized shame. They may fear failure or feel inadequate. That’s why celebrating the process of growth is essential:

Praise persistence: “You kept trying even when it was hard.”

Notice progress: “You stayed calm longer today.”

Avoid overemphasis on performance. Focus on courage, not correctness.

This reinforces the message: “Success isn’t about being perfect—it’s about showing up and growing.”

Together, these strategies help children rebuild the foundation of resilience—confidence, agency, and hope for their future.

Community and Professional Support

Healing from trauma is not a journey meant to be walked alone. While families provide the front-line care, professionals, communities, and systems must walk alongside them—offering resources, validation, and expertise.

Therapists and Trauma-Informed Clinicians

Mental health professionals trained in trauma and attachment can be a vital support:

Therapists help children process past pain through play, EMDR, or relationship-based therapies.

Family therapists can guide parents in deepening connection and understanding.

Occupational therapists and neurodevelopmental specialists help address sensory, emotional, and behavioral regulation.

Choosing a professional who understands the neurobiology of trauma ensures interventions are not only compassionate but effective.

Support Groups and Peer Networks

Sometimes, the most healing words a parent can hear are: “Me too.”

Support groups for adoptive and foster parents offer space to share, grieve, and grow.

Peer mentors or trauma-informed parent coaches can normalize challenges and share real-life tools.

For children, connecting with others who have experienced adoption or foster care reduces shame and builds identity.

No parent should feel isolated, and no child should feel like they’re the only one struggling.

Schools and Educational Allies

Schools play a powerful role in trauma recovery:

Trauma-sensitive classrooms adapt to emotional needs—offering structure, regulation breaks, and relationship-based discipline.

IEPs and 504 plans can include trauma-informed accommodations: flexible transitions, sensory supports, and emotional check-ins.

School counselors, teachers, and administrators become critical allies when trained to see behavior as stress, not defiance.

Collaboration between home and school creates consistency—children learn that support doesn’t end when the bell rings.

Child Welfare and Community Agencies

Adoption and foster care agencies, churches, community centers, and local nonprofits can:

Provide respite care, therapy referrals, parent education, and financial support

Organize workshops, camps, or events to strengthen family bonds

Advocate for trauma-responsive policies that put relationships before rules

When families are supported holistically, children thrive relationally, emotionally, and developmentally.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What are the guiding principles of trauma-informed adoption care?

Safety, trust, connection, and collaboration. These principles guide every interaction and intervention with trauma-impacted children.

2. How can adoptive parents implement trauma-informed practices at home?

Through predictable routines, emotional validation, co-regulation techniques, and relational repair. They lead with empathy, not control.

3. What training is available for providers working with adopted children?

Many trauma-informed care programs offer training on attachment, emotional regulation, and therapeutic strategies specific to adoptive families.

4. How does trauma-responsive care differ from traditional child welfare approaches?

It centers on understanding behavior through the lens of trauma and prioritizes healing relationships over punitive responses.

5. What system-level steps can support trauma-informed care for adoptees?

Agencies must train all staff in trauma-responsive care, adopt flexible service models, and actively partner with families to meet children’s evolving needs.

6. Why is acknowledging trauma history vital to adoption success?

Because unaddressed trauma creates barriers to attachment and trust. Acknowledging and working through trauma lays the foundation for long-term stability and healing.